This morning I read an interview with the very au-courant and hugely popular photographer Bastiaan Woudt by Marie Audier D’Alessandris, a gallery owner in New York (The Eye of Photography website January 25th, 2022). I read and re-read an answer to a question related to the colour Black several times:

The question: “… Black is a very recurring color in your work, in the sense of a very deep, very strong, very rich dark in your images, what is it in this color that you’re going after?

The answer, in part: “…. maybe it’s just part of the way that I process images and the way that I see, I really like to have a strong contrast in my images. But actually, it’s funny that you say that it’s like so black, because if you look in Photoshop it’s not totally black, it’s the same as the white parts in my images are never totally white…. these are all inspired of course by analog photography….”

At least Mr. Woudt is man enough to admit that it is all done in Photoshop. But, in a day and age where the Brazilian photographer Rafael Pavarotti is widely criticized for his ‘colour correction’ of 9 black models for British Vogue, where are we? Where should we stand on the use of digital manipulation. A lot of the criticism of the Vogue shoot was about the lack of differentiation/representation of actual skin-tone and the resulting sameness. I think we all agree that in reality everyone has a unique skin-tone, different one person to the next. It is not appropriate to offer a digitally manipulated sameness in the name of consistency of colour and presentation of clothes. When you view various photographs of the 9 Vogue models online, each one has their own skin-tone and each one looks entirely different, which is as it should be.

The question I have for Bastiaan Woudt – despite the fact that he shoots in digital and processes his work heavily in Photoshop – why are you choosing to present work where the skin-tones are so similar? There is a fake sameness one photograph to the next. Is it really possible to find models that are so alike, or is this more about sameness and presenting work that is so consistent to be unnatural and therefore in its imitation of living beings ends up being entirely about form and not at all about the model. Is it more about the clinical than the real? It is almost as though the model is an inconvenience.

It sadly feels like there is a certain Pantone number for near-black and another for near-white, and it is simply a matter of dropping in the digital file from the digital shoot and a second later extracting yet another like image, where composition – very good sometimes – is king and the sitter secondary, tertiary, or entirely irrelevant.

Skin-tones make photography interesting, it makes lighting – natural or cast by many lights – fun to play with and the results vary in intensity and strength, it is what makes capturing light so exciting. It is never the same twice. It seems this is missed entirely as the formula for Woudt-Photoshop-near-black and Woudt-Photoshop-near-white is generously applied. The result being a very predictable, repetitious and highly consistent seen-one-seen-them-all photograph. I look forward to seeing Mr. Woudt’s next body of work. With the compositional skills that Mr. Woudt clearly has, I am crossing my fingers and hoping for the best.

Harbel

Reflecting on a Small Chateau – Matheus Rose

Reflecting on a Small Chateau – Matheus Rose

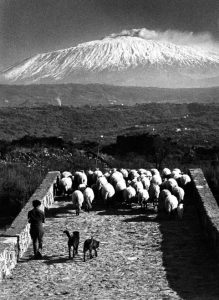

Edward J. Steichen – Rodin

Edward J. Steichen – Rodin Gertrude Kaesebier – le dejeuner sur l’herbe?

Gertrude Kaesebier – le dejeuner sur l’herbe?

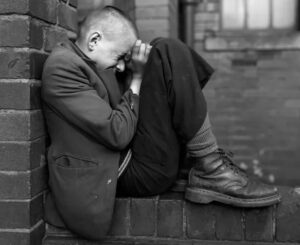

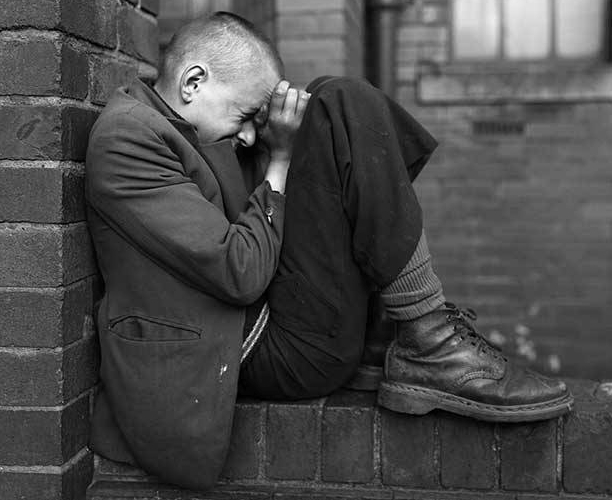

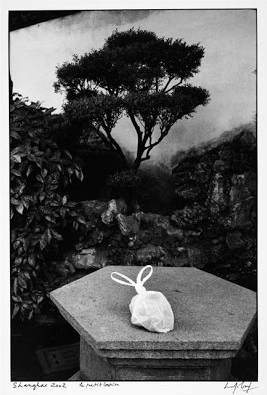

The dreamer. By Harbel

The dreamer. By Harbel