When the Marlboro Man met the hedge fund manager and his unscrupulous Art Advisor.

For a very long time, I have rejected the so-called ‘artists’ who appropriate and re-introduce someone else’s work as their own, which in turn, by way of the non-discerning eye of the opportunist art advisor, finds its way into the collection of a Wall Street hedge fund manager with more money to burn than a forest fire in Colorado. A collection where bigger is better and expensive is an attribute.

For the past 30-odd years I have followed the ups and downs of the judicial system, which has interpreted a single word: ‘transformative’ in any number of ways with wins and losses awarded to one side, or the other. More often than not, the victims have been photographers with great talent, but not so deep pockets.

There may finally be a glimmer of hope on the horizon. 2021 may well turn out to be a key year in the fight to take photography back from the copycats:

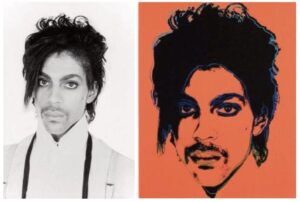

In August 2021, the photographer Lynn Goldsmith – probably best known for her portraits of musicians – was successful at the New York Second Circuit Federal Appeals Court, in her appropriation case against the Andy Warhol Foundation. The ruling overturned a lower court decision and states that Andy Warhol’s silkscreen of Goldsmith’s 1981 portrait of Prince was an appropriation and was not sufficiently transformative.

In December 2021, the New York art gallery Metro Pictures closed it’s doors for the final time. The gallery was opened in 1980 by Janelle Reiring, an assistant to Leo Castelli, and a partner. Metro Pictures legitimized appropriation, mostly at the expense of photographers, who did not have a chance to benefit from the collectors who made Metro Pictures a huge success. Not to suggest that the closing of a single gallery in any way changes what has been happening, but perhaps in a small way there is justice for the photographers who for years have tried to fight against overwhelming odds for their rights and their photographs.

Appropriation in the modern context probably originated with the ready-mades that the Dadaists exhibited. A urinal, a metronome, an iron. In the 1960s, things get a little fuzzy when Andy Warhol made Brillo Boxes and placed them in a gallery. More fuzzy yet, when Marilyn Monroe’s studio portrait was turned into the now famous silk screen series, along side Liz Taylor, Mao, Elvis Presley…..

I don’t know if it hinders or helps, but I think of ‘transformational’ as something more than taking a two dimensional image and changing it to another two dimensional image, where you can still recognize the original image. I don’t care if you go from colour to black and white, or the other way around; add paint; frame it, or unframe it; enlarge it, or shrink it; digitize it; re-photograph it…. If a photographer who in most cases has a difficult enough time making ends meet cannot count on society to protect her or his work, where exactly are we?

On March 1st, 2018, Richard Prince tweeted, attaching a photo of one of his Instagram appropriations: “Last night at LACMA. Artists don’t sue other artists. They get together, have a cup of coffee, argue, kick the can, hash it out, talk about Barnett Newman, and how aesthetics for an artist is like ornithology is for a bird.” Maybe, just maybe, 2022 is the year where the appropriated laugh last.

In his commentary on the work of 100 photographers called “Looking at Photography” Professor Stephen Frailey writes of Richard Prince: “Richard Prince’s work as a component of the hollowing of cultural authority is particularly perverse and savvy; the transaction from yard sale into the ranks of high culture, with the resounding approval of the financial market place.”

I guess the market speaks and the lemmings follow. Be that as it may, but answer me this: Where does Norm Clasen go to get his just rewards.

Harbel