In a recent article in the NY Times, Julia Jacobs reports that the self-governed Association of Art Museum Directors voted 54% in favour of allowing the sale from their collections to pay for the preservation of other parts of their collection. The devil’s advocate might wonder whether this means that the Chief-Curator and the entire curatorial staff can get paid from the proceeds of selling off a few unpopular works of art? Is this the classic slippery slope?

I can appreciate that the COVID19 pandemic had a major impact on museums and galleries across the world. With attendance and ticket revenue at zero for a number of months, a great many public museums relied on governments to step up and cover the shortfall. Loans, grants and one-time funding were part of the short-term life-raft that many institutions needed to survive.

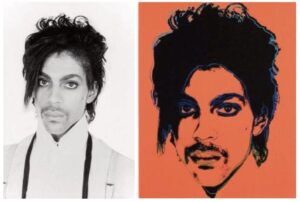

But this blog is not about the COVID19 pandemic, or museums struggling with attendance, but about whether the bond between the donor of work – often the artist – and the recipient of the donation – the museum – can be severed. Does a museum ever have the right to sell work that has been given, or acquired?

Is it a reasonable expectation that an artist who donates work to a museum can expect future generations to be able to view their work in perpetuity? While the museum may not be required to always have the work on display, is it a reasonable expectation that the work should at least be available from the stacks to be viewed by researchers, or other interested parties?

Many museum directors have voiced opinions about the new policy, but this is not a discussion for one museum, or the next, but rather whether it is a reasonable expectation on the part of the artist that forever actually means forever. That a gift is permanent and cannot be sold to either buy other work, pay salaries, or keep the lights on.

In a recent auction sale at Hindman in Chicago, the Houston Museum of Fine Arts sold a group of Eugène Atget Photographs. There was much celebration surrounding the successful sale. One might argue that in the photography realm, doubles of the same photograph exist and perhaps having the right to sell doubles would be acceptable, but where does this stop. The tip of the iceberg, perhaps?

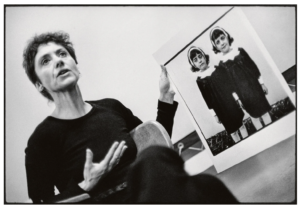

I know several photographers who are working feverishly not to leave their heirs the challenge of finding a home for their work. They are attempting to settles their estate during their lifetime and being happy in the knowledge that a gift to a great museum is going to give them and their descendents eternal peace of mind. However, the new policy from the Association of Art Museum Directors and perhaps future decisions by this self-governed association, may well suggest that any gift or donation, or acquisition comes with an * giving consent to unilaterally sell it later.

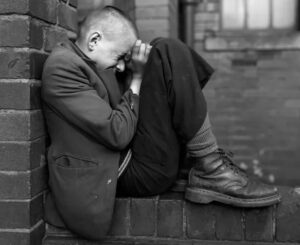

Imagine if a photographer’s work falls out of fashion, and can be sold to the highest bidder because a Director, or Board of Directors, says it is appropriate to do so to pay for the salary of a new curator, or a new frame for a work by another artist. What is a reasonable expectation?

Can one museum be deserving of our confidence, while others are ‘maybes’, and yet others are outright ‘high-risk’. What is the Government’s role in preserving our past and not bowing to trends, pressure groups, or political correctness. It is one thing not to show particular work, but selling it, or worse, is that a decision for the here and now, or is that a decision that we should happily kick down the road for future generations? There are no backsies, once a sale has been made. There is no coming back from a decision that in the future could be deemed poor, or even terrible.

Is it morally acceptable for a future Board of Directors of a given museum to sell off work with a simple vote by a temporary majority?

Harbel