Paul Hoeffler was my friend. We spent many a night discussing great Jazz musicians and his photographs over bottles of single malt whisky. Always Jazz music playing in the background, softly, as often Claire, his wife, would be giving piano lessons in the next room. Paul is virtually unknown outside a small circle of committed admirers, yet, he deserves so much more…..

I think back on the man that didn’t take the obvious photograph, but was more in tune than any other musician photographer, that I can think of. Paul knew music. He knew Jazz. His office and studio took up the entire living room in his traditional red brick house in Toronto’s Roncesvalles area. And unlike any other photographer that I have visited, Paul’s place was equally full of records, discs, reel tapes and recordings of every kind, and the boxes, and boxes of photographs and negatives that made you careful where you sat and vigilant about where you put down your whisky glass.

But first things first. I was introduced by my bank manager, who thought I knew something about marketing and perhaps could help one of his customers figure out what to do with a room full of prints and negatives. We met and I would say that had Paul been a sailor, I would have called him salty. He was in his early 60s when we met. Paul was born in 1937. And he was surrounded by a very large amount of stuff, which I think only he knew his way around. When we met, he had had a long career in places like Rochester, NY; New York City; Providence, RI, before moving to Toronto and settling down for keeps. I got the impression that he was sad at the state of the art of photography, in the sense that he felt that he no longer could get the access he needed to make the photographs that mattered. Too many managers, handlers, agents, security guards, fences and locked doors. He would often say things like: “those times are gone”, or “it is not like that anymore”. A little bitter perhaps. I don’t know, but a master of the highest order.

Paul studied photography at RIT, the famous Rochester Institute of Technology. Names like Minor White and passers by like Ansel Adams were the cast of characters that gave courses and instructed the young Hoeffler. RIT is of course located in the legendary city that spawned Kodak, and therefore seemed like a logical place to study photography. He started to shoot at virtually the same time as Tri-X film became the film of choice for consistent black and white photographs. As a young student one of his first assignments was a Jazz concert. And as they say, the rest is history.

Paul knew the music, almost as well as those playing it and he therefore knew where to be and where to focus during a performance. I was fortunate to work endless nights with Paul on a catalogue for an exhibition. A humble 24 page booklet, yet, I heard and re-heard stories that eventually got transcribed by me and became part of the catalogue.

I don’t think anyone will be able to find a copy of the catalogue today, so I will take the liberty of recounting a couple of the stories. Ones that have stuck with me.

Let me start with the 1955 meeting with Louis Armstrong. During a break in the concert at Rochester, Paul Hoeffler went back-stage and went into the dressing-room where Armstrong was holding court. I will leave the words to Paul, as I recorded them:

“Armstrong was there with a lot of fans and admirers. People would come up and say: ‘Louis, I am a little short, can you help out?’ He had his big roll of bills, and he would peel off a $5, a $10 or a $20. The place cleared out a bit and I was shooting some pictures. He had a bandanna around his head and he looked at me and said ’Oh, you might want to have a picture like this.’ He put his horn up to his lips and posed for me for several pictures. I had enough sense to shoot a few frames and stop and say: ‘Thank you, very much.’ I added; ‘Incidentally, in the movie last year, you played a tune called Otchi-Tchor-Ni-Ya. Would there be any chance of you doing that in the second half?’ Trummy Young the trombonist, was with him and Louis nudged to him and said: ‘Remember the movie we made about the white trombone player, Miller?’ Trummy smiled. ‘Remember the tune we played, Otchi-Tchor-Ni-Ya? Our friend here would like to hear that in the second half. Think we can do it?’ Trummy nodded. I thanked him very much and went out. For the second half of the program, I went into the pit right in font of the stage. The band came out. Armstrong played a tune and then spotted me. He nudged Trummy, looked at me and announced to the audience: ‘Last year we made a film about Glen Miller. And in that we played a tune called Otchi-Tchor-Ni-Ya. We have a special friend here tonight, who made a request to hear that tune, and right now we would like to play that and dedicate it to our friend.’ I was 17. I was floating.”

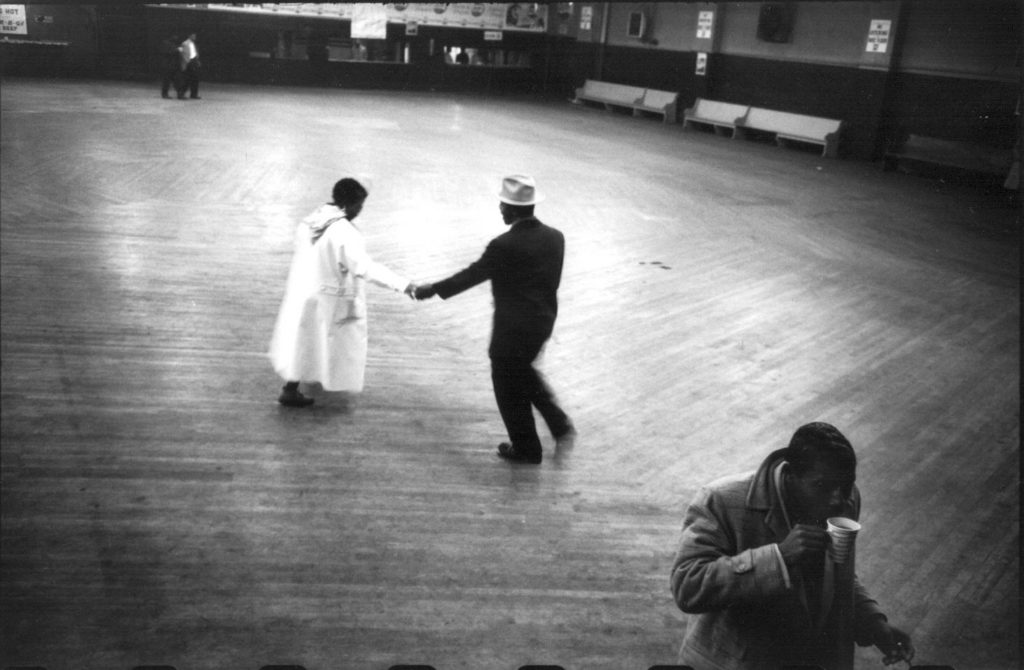

Paul was full of stories like this. He would tell me he was on stage with Erskine Hawkins and his band taking pictures, under the watchful eye of Julian Dash, the tenor sax player, who had suggested he stay close. He was the only white boy in the entire roller skating rink, and following a disgruntled girlfriend shooting a couple of rounds, apparently upset that her boyfriend had taken another girl to the dance, Paul understood and stayed close. Nobody was hurt. I don’t know if this explains how Paul had access, but he took photographs from under keyboards, behind drums…. That night, Paul shot the audience from the stage and produced what he often referred to as his Dream Dancing photographs. A little fuzzy, very moody, they show outlines of bodies moving around the dance floor. You can almost hear the music.

Finally, the one shot that I think says it all about how Paul worked. He was at a show with Count Basie and his Orchestra. He was, as usual in prime position, but he didn’t do the obvious, he photographed the wives and girlfriends waiting in the wings. Desperate for the show to end and their lives to begin again. It is a photograph with so much atmosphere and so much feeling, and at the same time an eye for what it was like being on the road, night after night putting on a great show.

I am often reminded of how Herman Leonard, or William Claxton photographed Jazz, and while Paul was in contact with many other jazz photographers, he was in my mind better. Unlike Leonard, who seems to desperately cling to a steady supply of cigarette smoke emanating from conveniently placed ashtrays, Paul didn’t need these tricks to make magic. He felt photographs.

I will probably write a couple more entries about Paul and his photographs. He passed away from cancer some years ago. Never a dull moment around Paul. He was full of stories, full of life and had a deep, very deep knowledge of the music and the musicians that he photographed. Paul Hoeffler, the Greatest Of All Time. I miss him.

Harbel