I admit it. I am using Deana Lawson to prove a point. I am taking advantage of a well-known and highly respected photographer’s work to illustrate how the usually black-clad, face-less critics and gallery owners describe a photographer’s work. I aim to show how descriptions are nothing more than elaborate word-salad – a hopeless sequence of adjectives and expletives – assembled for the benefit of the writer, and seemingly meaningless to everyone else.

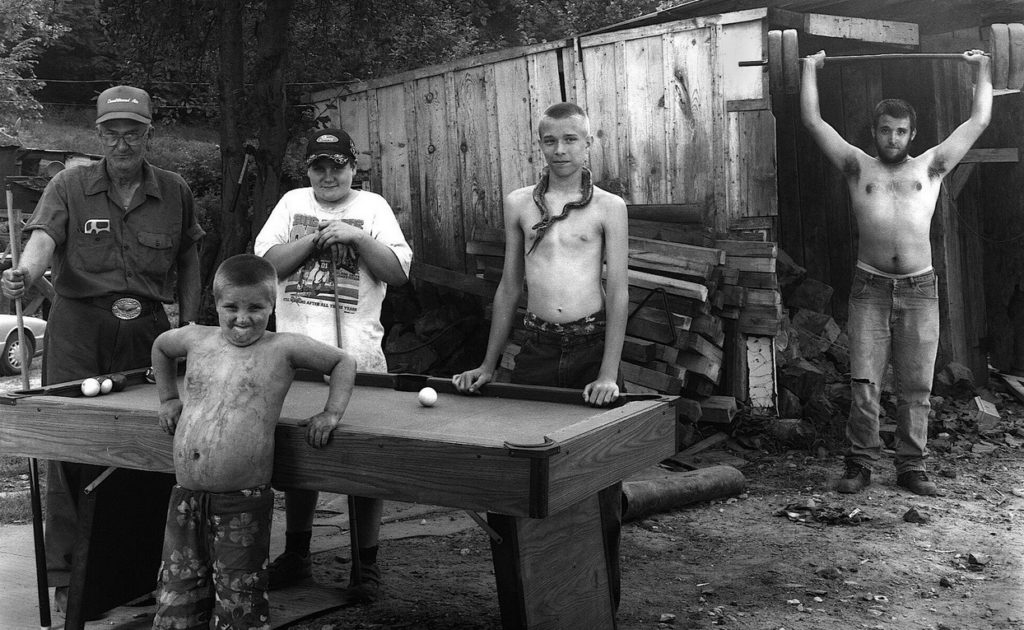

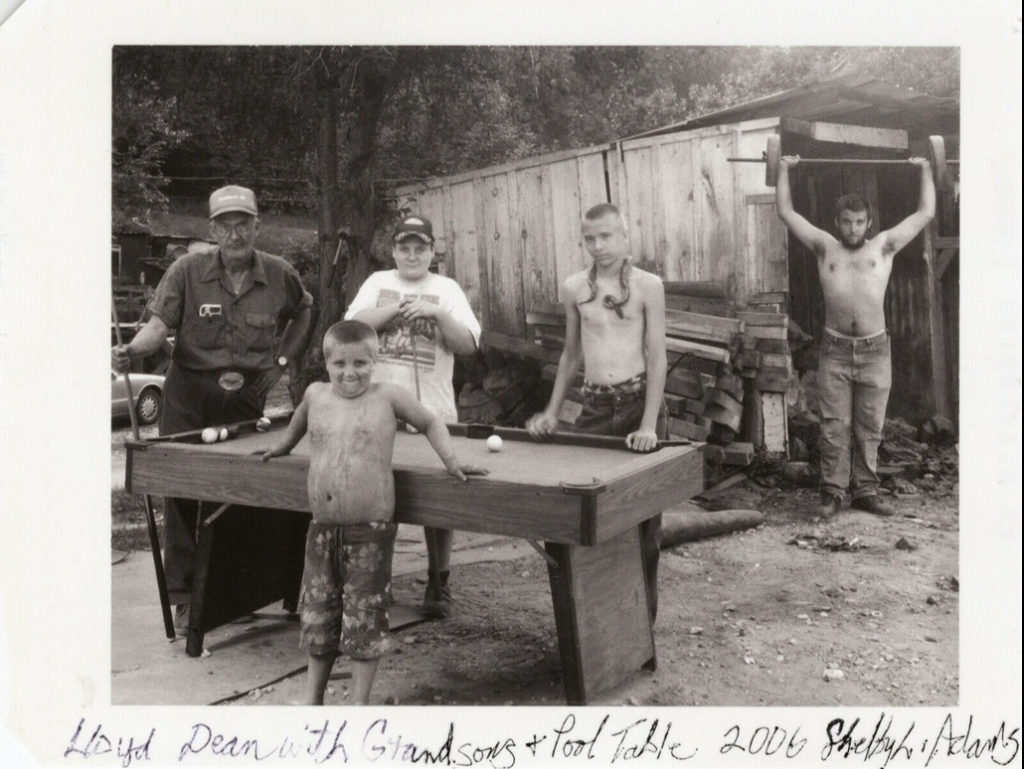

In the context of Deana Lawson, let me start by saying that I never stage photographs. I don’t ask people to stand or sit just so. I have only twice in my life asked a stranger whether I could take their photograph, and on both occasions I did not ask them to pose in a particular way, nor did I do anything but say ‘thank you’ after I made my photograph. As such, I really struggle with elaborate tableau photography with heavy direction and great control with nothing left to chance. By extension, I am not a great fan of Lawson’s work.

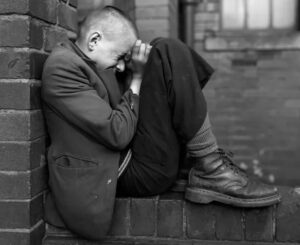

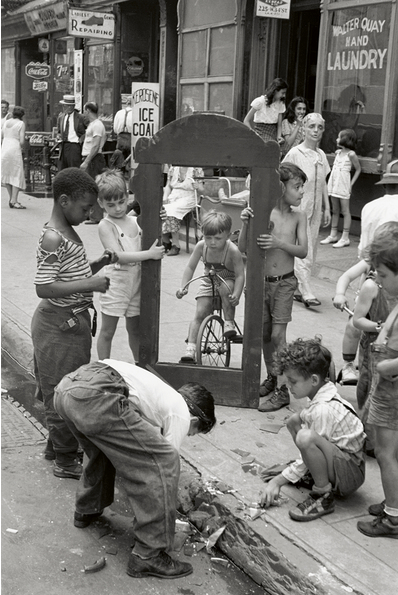

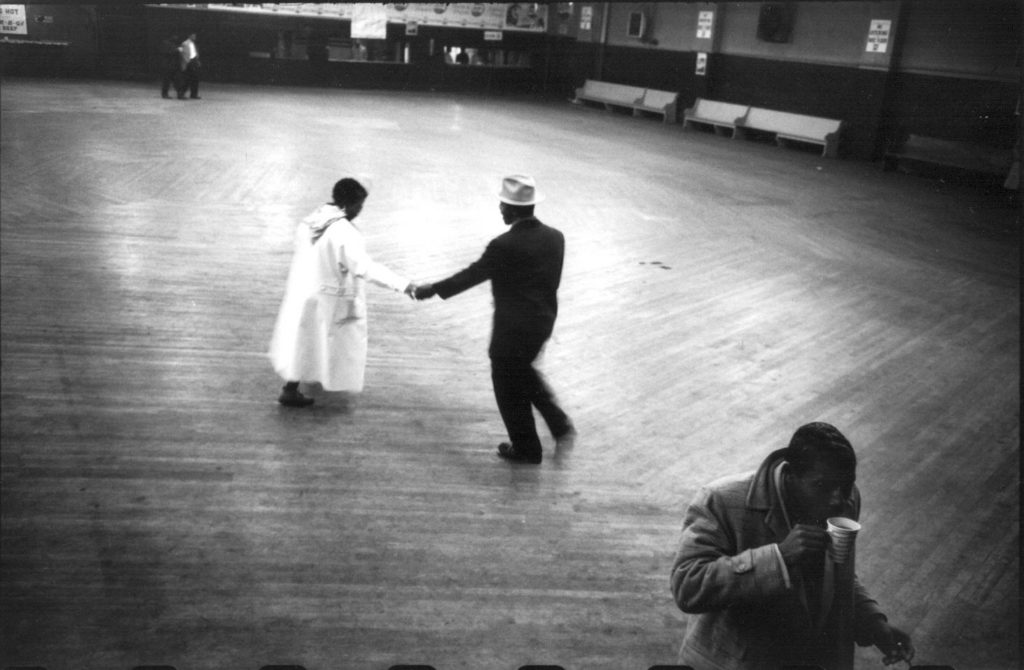

It is not that I cannot admire the skill of someone making such photographs, but I do find a more genuine approach by the photographer capturing a random moment in time through simple observation much more compelling.

Now, that I have revealed my bias, what I really want to write about is the way in which those that are in the business of displaying, criticizing, or selling art describe what is on display on the walls. This whole discussion started with a sentence I read in a newsletter announcing that the Gagosian Gallery is now representing Deana Lawson in New York, Europe and Asia.

I re-read the announcement twice and I still don’t understand what it means. Enter Mr. Google….. I did a search for Deana Lawson, I lifted the descriptive sentences found on the first couple of result-pages and dropped some of them in random order below, with the final entry being what started this whole process; the quote from the Gagosian Gallery press release.

In no particular order:

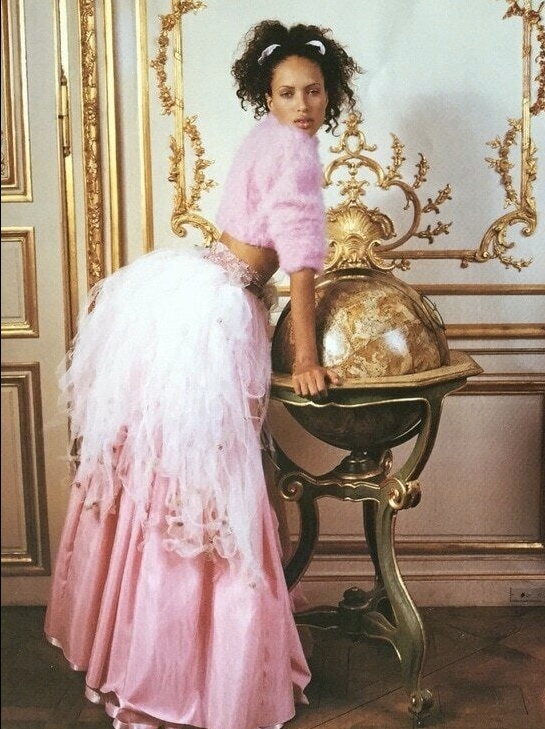

MoMA: “….saturated color continues to be a signature feature of Lawson’s practice, and in Roxie and Raquel the multiple yellows, whites, and blacks in the scene come together in a complex and compelling picture of family dynamics.”

Artsy.net: :Photographer Deana Lawson shoots intimate staged portraits that explore Blackness, legacy, and collective memory. Her pictures, which reflect both actual histories and contrived narratives, focus exclusively on Black subjects posed in richly detailed environments and interiors. “

Cat Lachowskyj for Lensculture.com: “These photographs contain multitudes — references to African diaspora, complex emotions, unspoken dreams, dignity, pride, love, visible scars, the trappings of household circumstance, the tenderness of generations.”

Wikipedia.org: “Deana Lawson is an American artist, educator, and photographer based in Brooklyn, New York. Her work is primarily concerned with intimacy, family, spirituality, sexuality, and Black aesthetics.”

Dodie Kazanjian for Vogue Magazine: “In her relatively brief career, Deana Lawson has become a Diogenes, a signifying truth-seeker of unviolated Black humanity and beauty.”

The Photographer’s Gallery: “Deana Lawson’s work explores how communities and individuals hold space within a shifting terrain of racial and ecological disorder.”

Gwendolyn DuBois Shaw: “Quoting Lawson: ‘Someone said that I’m ruthless when it comes to what I want. Maybe that’s part of it: I have an image in mind that I have to make. It burns so deeply that I have to make it, and I don’t care what people are going to think.’ Unfortunately, this kind of totalizing control isn’t good for anyone except Deana Lawson and the people who are making bank off it while blinding most of the art world to the consequences of this problematic artistic strategy.”

And finally, the Gagosian Gallery press release: “Lawson is renowned for images that explore how communities and individuals hold space within shifting terrains of social, capital, and ecological orders.”

I am finding the descriptions by the various institutions, websites, and critics really, really difficult to understand. I may not be a critic, and my command of the written language may be less evolved, but it is hard to imagine that the entries above are even about the photographs by a single artist!

I return to what I have said so many times in the past: Walk into a gallery, look at the photographs, make up your mind about what you are seeing, and only then read the labels, the gallery introduction, the catalogue, the critics. I know, this is not always possible if you are going specifically to enjoy something you have read about, or seen an announcement for, but try anyway, because we are so often pulled down rabbit holes that are not of our own making.

What we see and what we read in a photograph is deeply personal and has nothing to do with the intention of the maker, current trends, geo-politics, or anything else, or maybe it does for you. There should be no pre-judgement here. Simply enjoy the experience of seeing something and ‘reading it’ with your own lens and let others worry about where the work fits in the annals of art history, current culture, or artistic trends.

Harbel

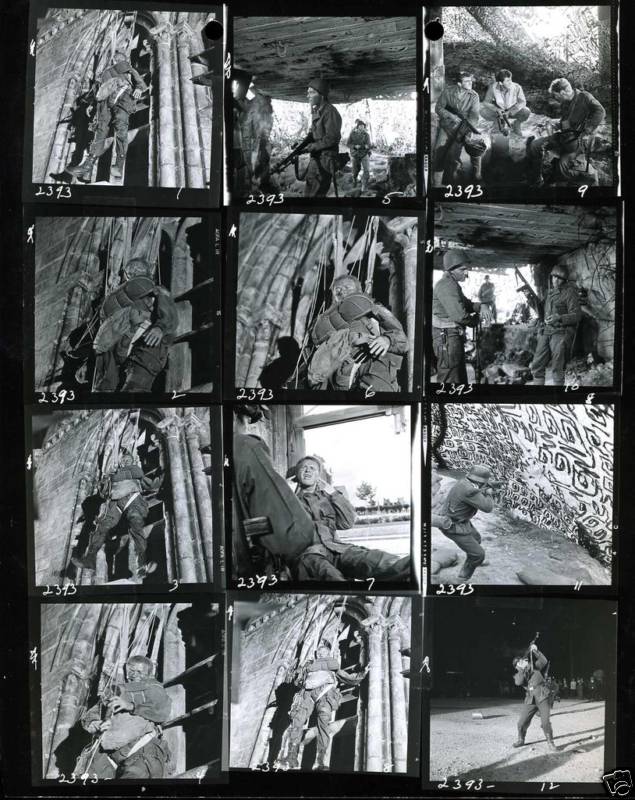

Andreas Gursky: Rhine II

Andreas Gursky: Rhine II Anonymous photographer: Rhine I

Anonymous photographer: Rhine I