What makes a great photograph? It is very, very personal. Books have been written, conferences held…. For me, I have learned that it can be a moving definition. It can change with time, but it is worthwhile to have a look at the process of becoming great.

I am going to turn to the French philosopher Roland Barthes. He wrote a book called “Camera Lucida.” It is a small book with a long philosophical discussion of the photograph. Barthes coins two terms that are worth remembering: ‘studium’ and ‘punktum.’

Pictures or images with studium are images that you notice. Think of all the photographs you are exposed to every day, ads on your phone, computer, television, billboards, photographs in newspapers, magazines, and so forth. Now, of all these impressions, which some now count as more than 3,000-5,000 a day, there is maybe one that you really notice. That image has studium.

A photograph with studium has the ability to capture your attention. It draws you in. It may play on your heart-strings, it may remind you of something, it may fill you with guilt, play with your mind. You may not like it; you may think it is horrible. Image creators know what works and what doesn’t (most of the time). Think babies, puppies, humour, sex, and so on. Studium you notice.

Punktum is when one of your studium images stays with you over time. These are quite rare. It is an image that comes back to you under certain circumstances, given certain stimuli.

You can probably think of images that you saw today that had studium, but probably not the ones from yesterday or last week. More importantly, you can likely think of images that have stayed with you and surfaced over and over again in your mind’s eye. They have punktum.

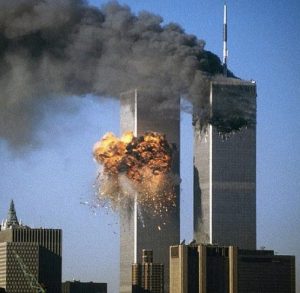

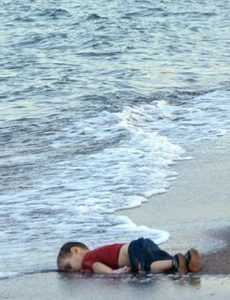

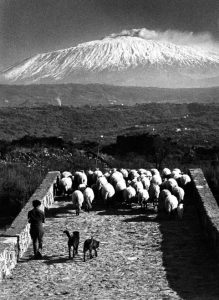

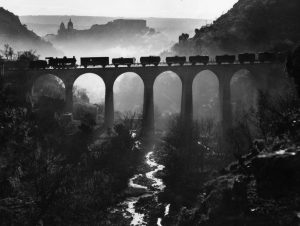

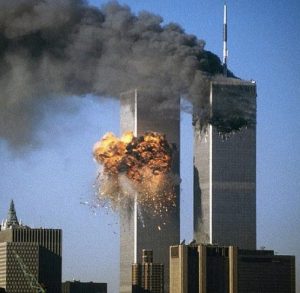

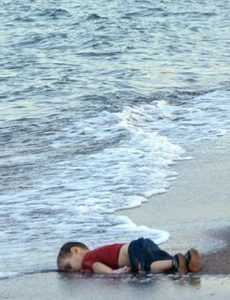

Let me give you some universal examples:

The dead migrant child on the beach in Greece; the Vietnam War photograph of the young girl running naked towards the camera following a napalm attack; the first man on the moon; the plumes of smoke on 9/11, etc. These are universal. I don’t have to show you any of these photographs; you have them stored in your mind, in full detail.

In addition to the universal images, there are punktum images that are particular to you. You know what they are. You may not be able to command them to appear before your inner eye, but given the right stimuli, they will show up, time and again.

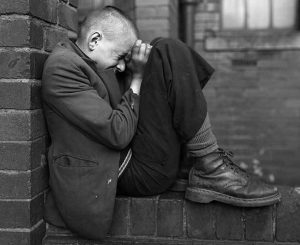

Among my personal punktum images, none are news photographs. This may be because I look for a particular skill in the photographer. In the simplicity or minimalism of the photographs, which has a particular appeal to me. No accounting for personal taste.

Both my examples are of a single figure, a portrait of sorts. The Horst P. Horst Mainbocher Corset was one of the first photographs I scraped together enough money to purchase. Made in 1939, it represents to me a daring, superbly lit figure from a time in photography, which was starting to move from recording fact, through early experimentation and surrealism to the mainstream. Made by the master of studio lighting, Horst, the photograph represents a very sensual rear-view of a corseted woman, with the ribbon loose and laying across a marble surface and in part hanging over the edge, where it catches the light beautifully. Revolutionary for the time, the model is photographed from behind and skirting, if not crossing, the line of what was permissible in print media at the time. An incredible image, which has remained with me since I first saw it in an art history class. I look at it every day and continue to be in awe.

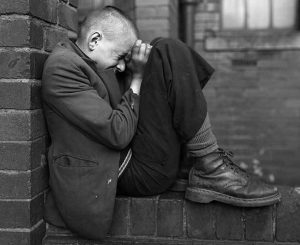

My second punktum image, is one that I call Boots. I am not sure what the proper title is. The photograph by Chris Killip, I first saw at the Rose Gallery in Los Angeles. It hit me as being an incredibly composed and lit photograph, but emotionally charged with what I believe is anguish and maybe desperation. To me, what hits home are the disproportionately big boots. I remember as a kid getting a shirt and jacket that were ‘to grow into’. These boots look like they are several sizes too big, maybe from a military surplus store. It is a photograph of desperation. I have seen many photographs of people that are down and out, but this boy, or young man is just too young to be this desperate. Every time I look at this photograph, my toes tighten in my shoes, I get goose bumps. I have had it hanging on my wall for several years now, and it still feels like a punch in the stomach every time I look at it. Punktum.

To address the idea that your personal punktum may change over time, I can say that Diane Arbus’ Boy with a Toy Hand Granade was the photograph that made me change my focus at university to Photography from Renaissance Art. The photograph had huge punktum for me, but has since lost its charge. Why? I saw the contact sheet from the shoot, and later read an interview with the boy in the photograph. In the Arbus photograph the boy looks like he is a person with a mental disability, which is very consistent with the outsiders that appear again and again in Arbus’ work. However, on the contact sheet, the boy looks like any other little boy playing in the park, and I do not like the fact that the photograph that Arbus selected from the roll, somehow misrepresents what was in front of her. It no longer resonates. It is like the Robert Doisneau photograph of the couple kissing at the Hotel de Ville in Paris, which I loved as the epitome of Parisian street photography, until I learned that it was staged with two actors…., but that is another story.

I must have seen millions of photographs in my time as a photographer and collector, and if you asked me to draw up a list of photographs that had punktum for me, I might get to 25 or 30. Some of these I have on my wall. Some I would dearly love to hang on my wall. Some I will never have, because they are either sitting in a museum and not available on the open market, or I simply cannot afford them. Others, despite their punktum, I don’t want. They might be gruesome, or too difficult to look at and live with. I am fortunate to have a few punktum images in my collection that I love and would never part with. This is the power of punktum.

Harbel,

Copenhagen

See more on my website: harbel.com

Images are borrowed from the web and are for illustration purposes only, no rights owned or implied.