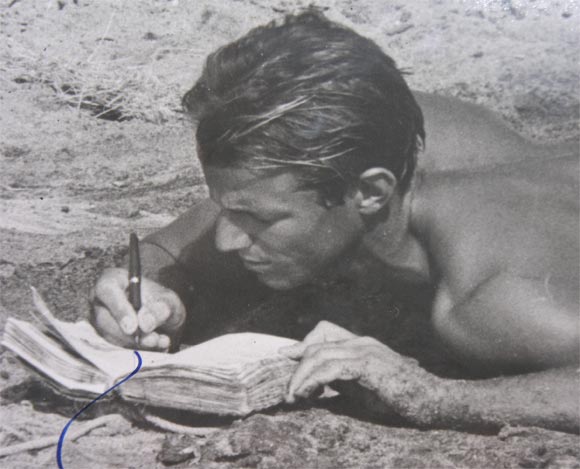

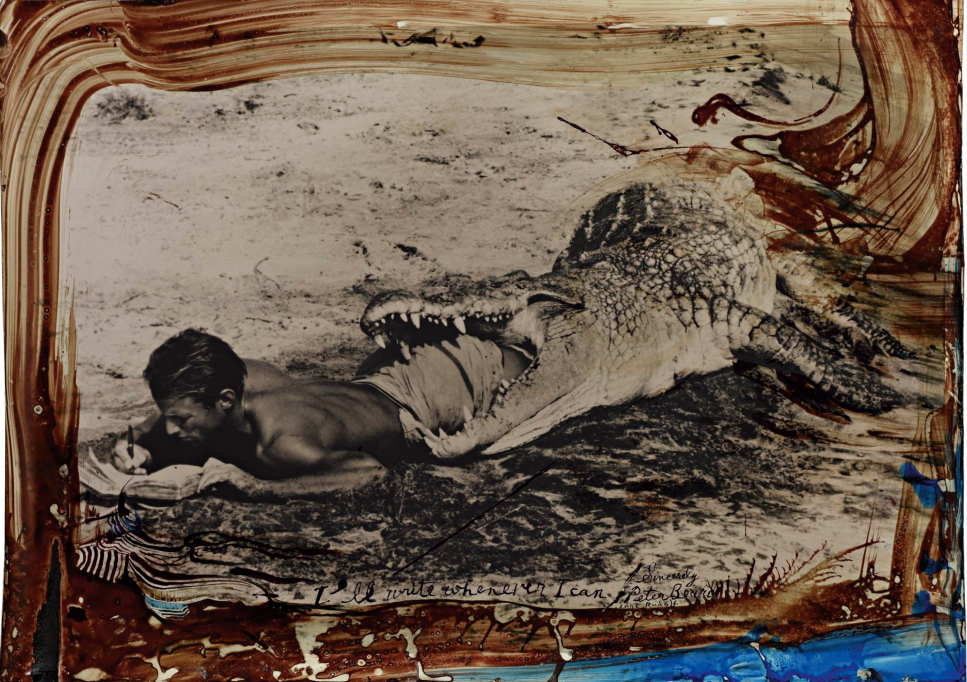

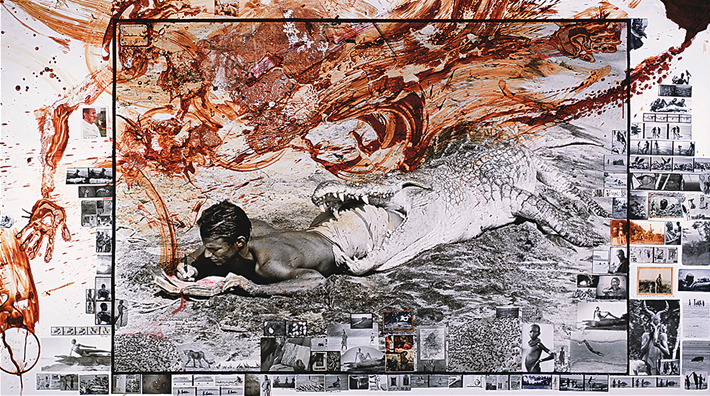

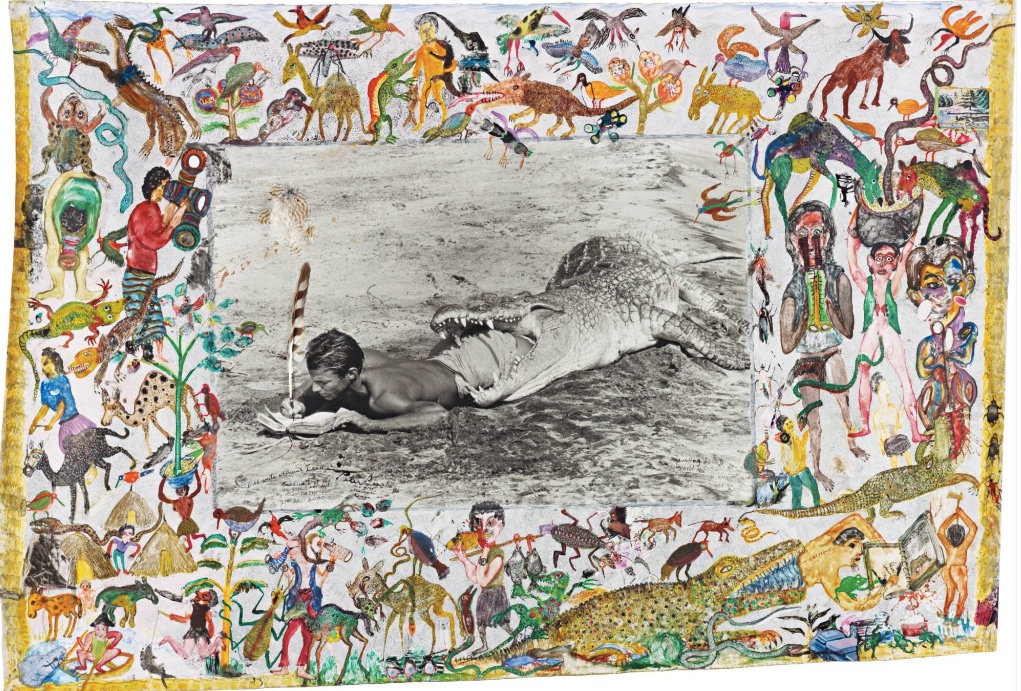

‘I Will Write when I Can’ (detail)

One of the reasons I got into photography, both as a shooter and as a collector was Peter Beard’s connection to Karen Blixen, or as she is known in large parts of the world, Isak Dinesen, her nom de plume. Karen Blixen was still alive when I was young, she died in 1985. By 1991 her home, north of Copenhagen, had been made into a museum. I was on vacation in Denmark and went there soon after it opened. There were a couple of references to Peter Beard at the museum and I started looking into the connection. I was interested in photography and had read Out of Africa as a young man. The combination was irresistible.

As often happens to me, I went from one fascination to another. Blixen led me to Beard, which in turn led me to read and collect first books and then through a stroke of pure serendipity a few prints by the great photographer. I will not bore you with a biography of Beard, there are lots of obituaries around these days, and no doubt there will be lots of features in magazines and future retrospectives to come at museums and galleries around the world. But, suffice it to say that he was so enamoured with Blixen that he made his way to Africa by way of Denmark, eventually using some of his vast inheritance to acquire land next to the property, where Blixen so desperately had tried to grow coffee. He named it Hog Ranch.

In Kenya, it seems, Beard found his proper identity. He photographed, lived an explorer’s life, shooting mostly with a camera, as opposed to a gun, and capturing wildlife and the people that co-exist with them. He famously worked on a book, which he in 1965 presented to the White House as his last call for the protection of wildlife in Africa. Particularly East Africa. Beard seems to have been on a mission, I suspect one that he only realized was there once he got to Kenya in pursuit of the exotic and dream like qualities he had read about and had seen pictures of. With a healthy trust fund in his back, he could afford to live a lifestyle that most can only dream about. Though coming from near NY royalty, he seems to have been more comfortable living in a tent and walking around in a worn pair of shorts with a camera around his neck in the hills above Nairobi.

An explorer by nature, I think, he probably thought of himself as being born too late. Longing for a time when the Empire was in full bloom and Kenya an outpost of the British-ness. He probably identified with Finch-Hatton and all the other characters that would work their way through the hills from trophy to trophy, once in a while coming back to Nairobi to drink at the club and share war stories of what they had felled with a single bullet, and what got away.

Beard’s work is interesting in that he really has only one body of work that anyone takes seriously, that being made prior to the publishing of the 1965 book. There were the odd commercial projects to follow, but he kept going back to what he was known for. Reworking and rethinking and retouching and adding to the East Africa animal photographs that we have all come to love and appreciate.

A family member told me that there were two major tragedies in Peter Beard’s photographic life. The first when his house in Manouk burned down with a lot of his prints and negs lost forever. This is well publicised. The second episode is not so well known…. Beard had been married to Cheryl Tiegs for a while and had apparently been given many, many warnings, but Peter was hard to tame and got home at dawn one day to find a smouldering pile of negatives on the front lawn.

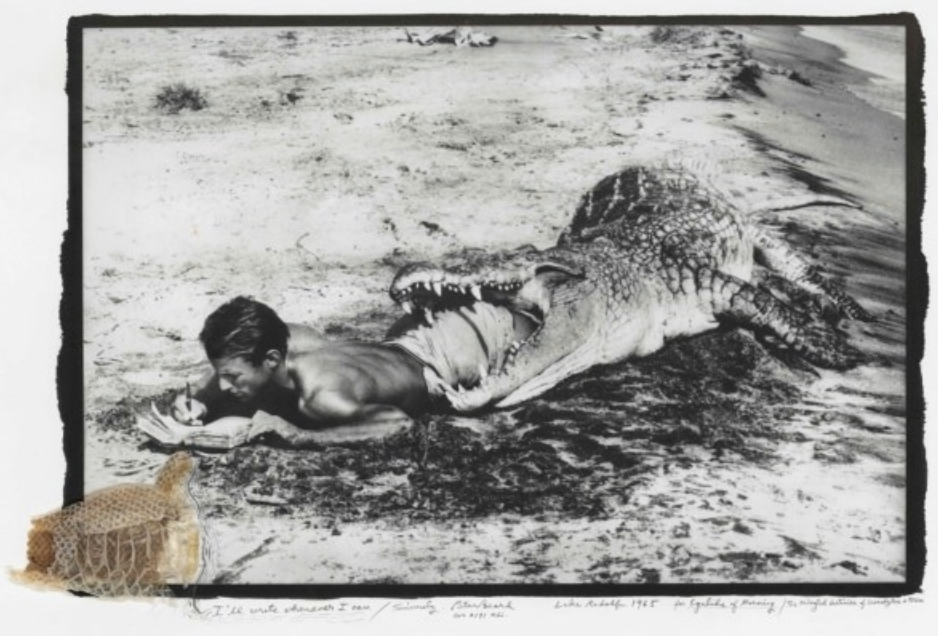

One theory for why Peter Beard took to making his colourful collages and adding to the beautiful photographs that he had made in the early 1960s was that he needed to camouflage the fact that his photographs were copy prints from old photographs, because the negatives no longer existed. You can as a purist of course lament this, but you have to give credit to the creative and often beautiful way in which Peter Beard decorated his images. Using found objects, cut-outs from magazines, Polaroids, blood, sometimes from the butcher and sometimes his own, hand prints, foot prints, and so forth. He would draw little figures of animals and men, colourful images drawn from a creative mind that had been making collages and had kept diaries with cut-outs from an early age.

I only met Peter Beard once. In Toronto. He was there for an opening of a gallery show and had been given free reign on the normally white walls. I was the last visitor through the door the day after the opening and he happened to still be there. I said ‘hi’ and asked if he would sign a book for me. Peter was as usual in bare feet and covered in indigo ink. His feet were somewhere between black and blue. The black from walking around barefoot, the blue from ink. He decorated surfaces normally white with prints of feet and hands and little scribbles. Funny figures that reminded me of a children’s drawings. Colourful and cartoon like. He not only signed a book for me, he decorated the first couple of pages with hand prints, a drawing of an alligator, a speech bubble by the fetus of the elephant that he had photographed that was on the title page. A personalized greeting to a guy he had no idea who was, whom he took the time to create a little work of art for. He was kind, friendly and very comfortable in his own skin. Notoriety and fame did not seem to change him. He was focused on you, and while he had done his little show countless times over the days and weeks of exhibitions he had had in various places, he took the time to make the experience personal for me. I will never forget that.

Some time in the early 90s, I bought an 11×14 print of ‘I will write when I can’ Lake Rudolf 1965. It is the classic Beard photograph that we have all seen of him lying in the mouth of a huge crocodile writing in his diary, looking all serious. There is a hand drawn ink line – indigo of course – drawn to the open area below the crocodile, where he wrote the title, signed it and dated it. It has been among my most treasured photographs for a very long time. I have shown 4 versions of this image in this entry, to give you an idea of the versatility and creativity of Peter Beard.

Peter was 82, when a couple of weeks ago he walked away from his home in Long Island. He was found 16 days later a mile away in a forested area. Those that knew him had been speculating and hoping – despite the odds – that he had gone on one last expedition. And maybe he did. Rest in Peace, Peter Beard. King of the Jungle.

Harbel,

April 20, 2020