At the risk of yet again sounding like a broken record to those that read my blog from time to time, I cannot help it. This morning I was looking at the various newsletters that I subscribe to and came across the work of Lisa Kristine. A photographer, whom one can only admire with her commitment to end slavery and her desire to document the world, often of those less fortunately than ourselves. In the lead-in to her short answer questionnaire on The Eye of Photography, her first experiences in the darkroom with her uncle….. perfect…. I really want to love her work!

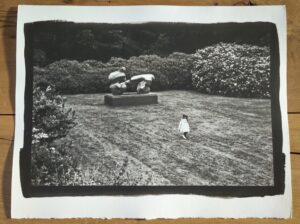

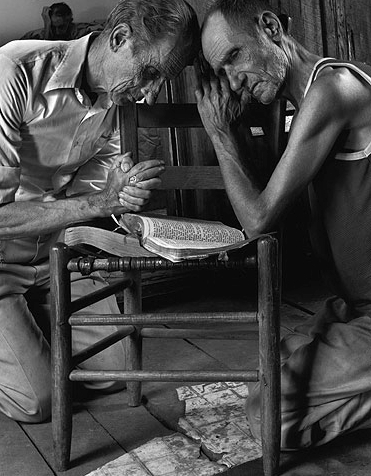

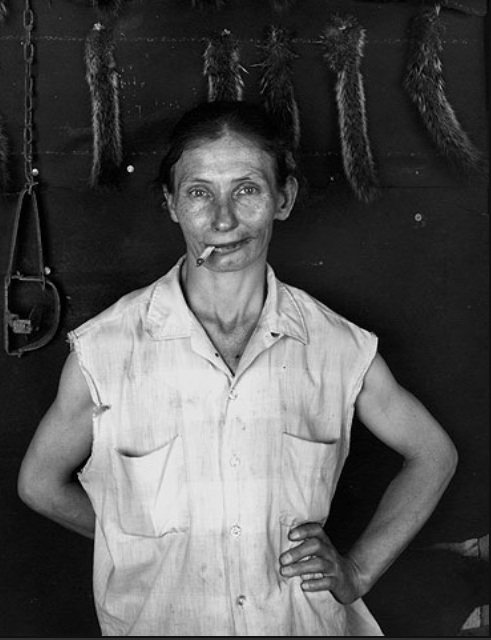

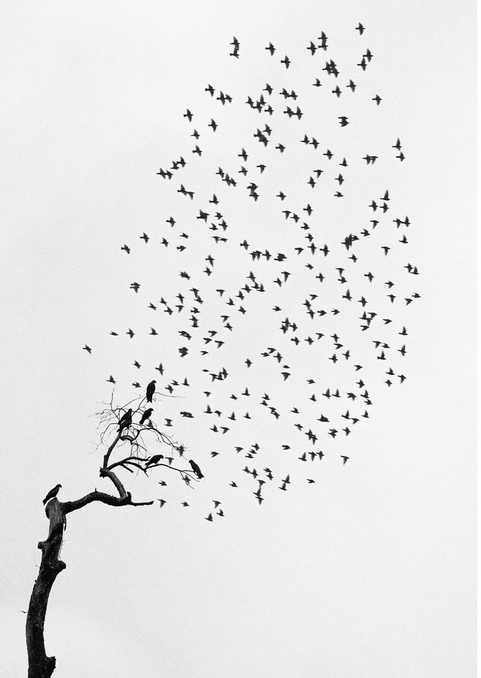

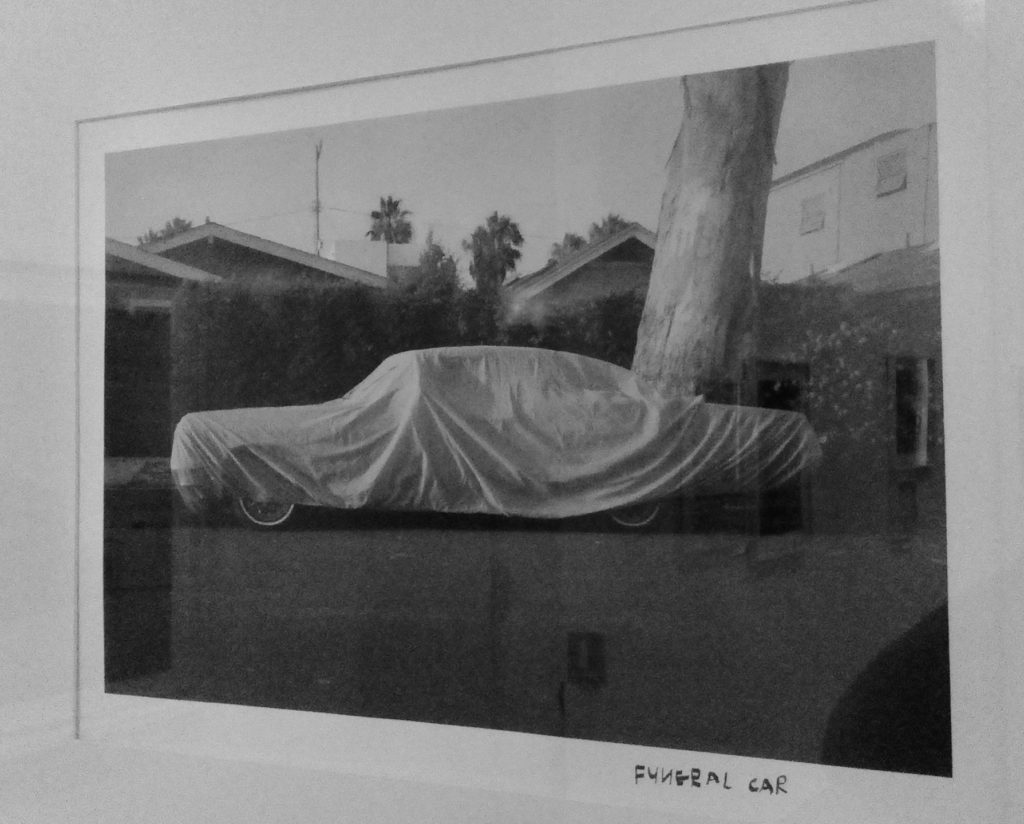

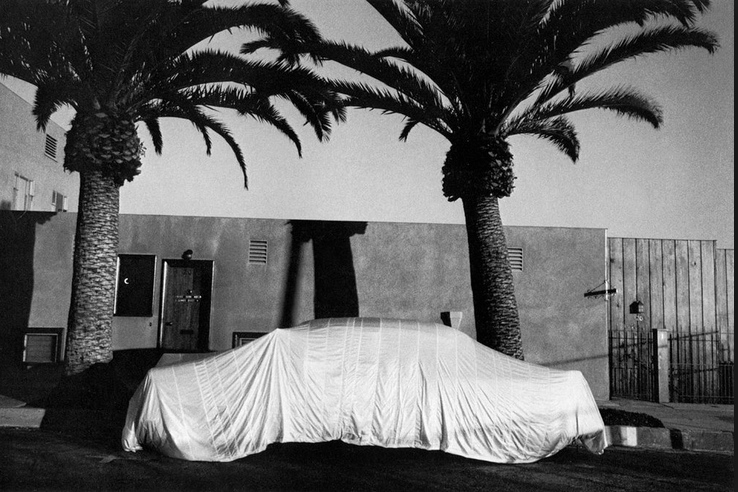

Normally not a super fan of colour work, Lisa Kristine’s colour images are both arresting and very strong. Her compositions are terrific and the impact is both hard hitting and beautiful, all at the same time. However, in the two black and white images that I found – shown here – there are some inherent challenges, which I think are symptomatic of the time in which we live.

Turning the real into the unnatural

Painters face an eternal question. When is the painting finished? The canvas sits there on the easel. The painting is fabulous. The painter holds the brush and is trying to make it better. The tiniest of brush strokes that will surely take the painting even further. The temptation is always there to do that little bit extra, correct that little something that you are sure everyone will notice, but only you can see. That little bit of magic that will forever change the work to your best. Some need others to say when enough is enough, when finished is truly finished and the work cannot get any better.

In the digital darkroom, the situation is much the same, but the temptation often overwhelming. I have written about Steve McCurry’s photographs and the choices of National Geographic Magazine, as well as several others who have taken it too far, under various guises. Knowing when to stop is equally as important to the photographer, as the painter.

I know my eye is sensitized to black and white photography, which I freely admit that I prefer. I won’t comment on colour saturation, or try to insert myself into what should or should not be done in colour work, but what I have trouble with is the excessive light and shadow in black and white work. The two examples here are in my view past the point of what one might achieve in optimal conditions with an analogue camera and film, or for that matter what one might see with the naked eye. I think this is at the expense of the message and the reality that the work tries to represent.

Am I really the only one that finds it hard to look at these super bright, hyper-unrealistic photographs that can only be born from software. They do not exist in the natural world and are purely the result of a need to make excellent impossibly better!

Harbel

(may not be reproduced in full, or in part without the written permission from the author)